Introduction

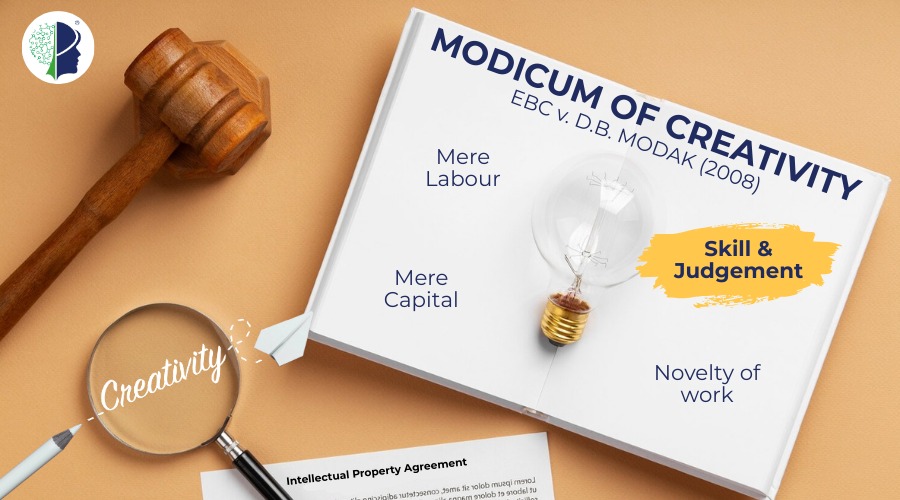

Can adding paragraph numbers to a judgment create copyright? That was the real question before the Supreme Court in Eastern Book Company v. D.B. Modak (2008). In copyright law, “original” doesn’t mean novel like a patent, or unique like in our everyday language. It means the work has to be created by the author and not copied. The more serious question is how much of the author’s own effort is considered enough for it to count.

In this case, the Court got the opportunity to decide whether the editing and formatting publishers add to raw judgments such as headnotes, paragraphing and cross-references deserved copyright. The ruling set the baseline for what “originality” means in Indian copyright law and what businesses can protect.

Case Background: Eastern Book Company v. D.B. Modak (Facts and Issues)

Eastern Book Company (EBC) is a leading Indian legal publisher that publishes Supreme Court Cases (SCC). Since 1969, SCC has published judgments but not as raw text. Editors added value through headnotes, paragraph numbers, footnotes, cross-references and analytical notes, making SCC a trusted research tool.

In the early 2000s, rival companies – Spectrum Business Support Ltd. and Regent Datatech Pvt. Ltd, launched software containing Supreme Court judgments. EBC alleged they copied not only judgments in the public domain but also SCC’s added features such as formatting, headnotes and paragraphing. EBC then filed a copyright infringement suit.

Issues before the Court

- What should be the standard of originality for copy-edited Court judgments treated as derivative works, and what level of contribution is required for such derivative works to qualify as “original” under the Copyright Act, 1957? In other words, what level of originality must edited judgments have to qualify as protected works under the Copyright Act, 1957?

- Whether the entire copy-edited version of judgments published in SCC qualifies as an original literary work due to the “inextricable and inseparable admixture” of the copy-editing inputs with the raw text, or whether copyright subsists only in specific inputs inserted by the appellants. In simpler terms, Does copyright protect the entire edited judgment or only the added editorial inputs?

Arguments of the Appellants

- While raw judgments of Supreme Courts are in the public domain, the copy-edited versions published in Supreme Court Cases (SCC) involved the exercise of independent skill, labour, and capital, making them derivative works entitled to copyright protection.

- Section 52(1)(q)(iv)does not prevent copyright in independently edited and formatted versions of a judgement produced by a private publishers.

- Originality should be judged based on the work as a whole, not by separating and then evaluating individual Inputs. They argued that these inputs like headnotes, cross-references, classification of dissenting and concurring opinions, and formatting etc, together with the judgement created a distinctive work.

- Copyright does not require “literary merit” or creativity in the sense of patent law. As long as the work is not trivial or purely mechanical, and involves sufficient skill and judgment, it deserves protection.

- Allowing others (like the respondents) to copy their edited versions would amount to misappropriation of their investment, discouraging effort and innovation in publishing law reports.

In simpler terms, EBC’s position was that Editing takes real skill and judgment. Headnotes, classification and formatting transform raw judgments into a distinct work that deserves copyright.

Arguments of the Respondents

- Judicial decisions are in the public domain, and no one can monopolize them through copyright claims. Section 52(1)(q)(iv) reflects this principle of free accessibility.

- the Appellants’ inputs were merely mechanical or clerical, involving no originality in the copyright sense.

- Granting copyright over such minor editorial work would allow private publishers to restrict public access to the law, which is contrary to public policy.

- Copyright law protects works showing creativity, not mere labour. Since SCC’s inputs lacked a “creative spark,” they could not claim copyright.

- Recognizing copyright in edited judgments would create monopolies in legal publishing. Free competition requires that others should be free to compile, arrange, or format judgments independently.

In simpler terms, Respondents’ position was that Judgments are public property. Minor edits like numbering or formatting do not show originality. Granting copyright here would privatise access to the law

The Supreme Court’s Analysis and Decision

The Court rejected both extremes. It declined to protect mere effort under the “sweat of the brow” doctrine and also declined to require a high threshold of creativity. Instead, it adopted a middle path known as the “skill and judgment” test, following Canadian precedent.

The judges noted that under Indian law, “original” doesn’t mean novel or inventive; it essentially means that the work originates from the author (it is not copied). But that alone begs the question that how much input from the author is enough to say the work originates from them and isn’t just a trivial variation of something already existing?

The Court coined a memorable phrase, saying the derivative work must have a “flavour of minimum creativity.” This “flavour” basically means you should be able to perceive some personal contribution of the author that makes the resulting work “somewhat different in character” from the raw materials.

Conclusion of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court held that clerical edits such as correcting spelling or punctuation, inserting paragraph breaks, etc were too trivial to qualify for copyright protection as they lacked originality. But substantive inputs such as drafting headnotes, numbering and cross-referencing paragraphs, identifying concurring and dissenting opinions, etc involved sufficient exercise of skill and judgment, and therefore meet the threshold of originality required for copyright protection.

Our remarks

EBC v D.B. Modak (2008) clarifies the most fundament aspect of copyright law, highlighting the legal criteria for securing copyright protection, and envisaging that the work must have a “flavour of creativity”.

For publishers this means that editorial enhancements such as headnotes and indexing can be protected while raw content remain free.

For businesses the lesson is broader. If you are compiling or curating, copyright protection comes only with a “flavour of minimum creativity.” Labour without judgment is not enough.

Practical tip: If your work involves repackaging public information, whether through research reports, compilations or databases, ask yourself three questions before relying on copyright:

- What have we added that reflects judgment rather than just effort?

- Could another person reach the same result through purely mechanical work?

- Is there a visible spark that makes our version stand apart?

If the answer to all three is yes, your content is more likely to qualify as original and defensible.